|

Many groups of literary manuscripts are found in the Manuscripts Collection, including the papers of Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, John D. McDonald, Carl Hiaasen, Ernest Mickler, and Frank O'Connor.

One of our most significant and extensive collections is The Zora Neale Hurston Collection. After Zora Neale Hurston died on January 28, 1960 in a Fort Pierce, Florida, hospital, her papers were ordered to be burned. A law officer and friend happened to pass by the house where she had lived, stopped and put out the fire, thus saving an invaluable collection of literary documents for posterity. Mrs. Marjorie Silver, friend and neighbor of Zora Neale Hurston, gave the nucleus of this collection to the University of Florida libraries in 1961. Frances Grover, daughter of E. O. Grover, a Rollins College professor and long-time friend of Hurston's, donated other materials in 1970 and 1971. In 1979 Stetson Kennedy of Jacksonville, who knew Hurston through his work with the Federal Writers Project, added additional papers.

Photograph of Zora Neale Hurston (center) and

friends, taken outside her home in Fort Pierce, FL

ca 1959

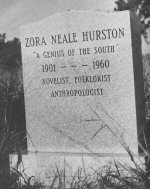

This badly damaged and charred photograph is the last known image of Zora Neale Hurston. Zora Neale Hurston died indigent and largely forgotten in 1960 in Ft. Pierce, Florida. The reestablishment of her reputation was sparked with a 1979 article by novelist Alice Walker in Ms. Magazine. In 1973, Walker had raised a gravestone to mark Hurston's burial place with the inscription: This badly damaged and charred photograph is the last known image of Zora Neale Hurston. Zora Neale Hurston died indigent and largely forgotten in 1960 in Ft. Pierce, Florida. The reestablishment of her reputation was sparked with a 1979 article by novelist Alice Walker in Ms. Magazine. In 1973, Walker had raised a gravestone to mark Hurston's burial place with the inscription:

ZORA NEALE HURSTON ZORA NEALE HURSTON

"A Genius of the South"

1901 - 1960

Novelist, Folklorist

Anthropologist

She was actually born in 1891. Confusion over her birth date is part of the controversy and ambiguity that surrounds so much of her life and career.

This small exhibit attempts to demonstrate a small part of Hurston's role as a Florida folklorist and novelist, and the bridge she made between the two crafts

Hurston Papers Burned

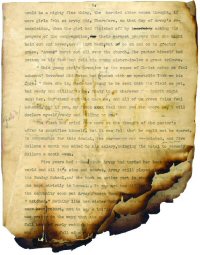

Hurston died January 28, 1960, confined by reason of health and financial status to the St. Lucie County welfare home. Following her death, her remaining property was ordered burned. After the fire had been started, Patrick Duval, a friend and Saint Lucie County deputy sheriff, came upon the fire, extinguished it, and saved many of her papers and manuscripts, later acquired by the University of Florida. This photograph and the manuscript of Seraph on the Suwanee are among the documents saved from the flames. Hurston died January 28, 1960, confined by reason of health and financial status to the St. Lucie County welfare home. Following her death, her remaining property was ordered burned. After the fire had been started, Patrick Duval, a friend and Saint Lucie County deputy sheriff, came upon the fire, extinguished it, and saved many of her papers and manuscripts, later acquired by the University of Florida. This photograph and the manuscript of Seraph on the Suwanee are among the documents saved from the flames.

Also saved was the manuscript of an unpublished biography of Herod, the Great. Fortunately she had earlier donated some of her manuscripts to the James Weldon Johnson Collection of Yale University. The location of other manuscripts, including unpublished works are unknown and perhaps were burned beyond saving.

Is it She, or isn't it?

Photograph of Zora Neals Hurston(?)

by Alan Lomax, Eatonville, Florida, 1935 Is it She, or isn't it?

Photograph of Zora Neals Hurston(?)

by Alan Lomax, Eatonville, Florida, 1935

Controversy seems to pervade all aspects of Hurston's life, even her photographs.

In addition to having been raised and having lived in Florida much of her life, Hurston made several professional journeys through the Sunshine State. In 1935, she was a member of a Recording Expedition to Georgia, Florida, and the Bahamas with Alan Lomax and Mary Elizabeth Barnicle.

This photograph, taken in Hurston's hometown of Eatonville, Florida, during that expedition, is one of the most popular Hurston photographs, having been published many times and used, as here, for promotional purposes. Recent research indicates, however, that the photograph may not be of Hurston, but of an unidentified Eatonville woman, but uncertainty remains. The photograph will doubtless continue to be identified as Hurston's.

Hurston and the Florida Federal Writer's Project

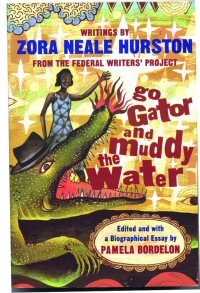

Go Gator and Muddy the Water

Pamela Bordelon, ed. New York: Norton, 1999.

In 1938, Hurston took employment as a writer with the Florida Federal Writers' Project. She was assigned as a staff writer to the Negro Unit in Jacksonville and worked primarily on a proposed book on the Negro in Florida. In this role, she produced numerous essays. Typescripts of two are shown here. The project was never completed. A book of writings from it was finally published in 1993, but did not contain any of Hurston's contributions. Hurston's FWP writings were not fully published until they were collected in Go Gator and Muddy the Water. In 1938, Hurston took employment as a writer with the Florida Federal Writers' Project. She was assigned as a staff writer to the Negro Unit in Jacksonville and worked primarily on a proposed book on the Negro in Florida. In this role, she produced numerous essays. Typescripts of two are shown here. The project was never completed. A book of writings from it was finally published in 1993, but did not contain any of Hurston's contributions. Hurston's FWP writings were not fully published until they were collected in Go Gator and Muddy the Water.

Some of Hurston's work was published in the Florida volume of the American Guide Series (1941), the most noteworthy of Federal Writers' Project publications.

Florida Folklore

"Go Gator Muddy the Water," typed manuscripts from the Hurston Papers of the University of Florida.

This essay is an early draft of the title essay in Go Gator and Muddy the Water. Hurston explains the origins and development of folk songs and stories, giving numerous African American examples, including stories of Big John de Conquer, "culture hero of the American Negro folk tale."

Cross City

PHOTOGRAPH OF ZORA SMOKING taken by Robert Cook, or Stetson Kennedy. Cross City, Florida. 1939. PHOTOGRAPH OF ZORA SMOKING taken by Robert Cook, or Stetson Kennedy. Cross City, Florida. 1939.

As a member of the Florida Negro Book project, Hurston made a field trip to Cross City, Florida in 1939, to gather life histories of workers at the Aycock and Lindsay turpentine plantation. A white supervisor and photographer joined her. This photograph has been attributed both to Robert Cook, the team photographer, and to Stetson Kennedy, himself a well known Florida writer and a supervisor with the project. Kennedy has described coming upon Zora sitting on the porch of a turpentiner's shack and taking a candid photo of her "rocking and smoking."

Turpentine Camp

"Cross City: Turpentine Camp," typed interview notes from the Hurston Papers, University of Florida.

Hurston's interview notes from the turpentine camp have been preserved. The pages shown here indicate the rough lifestyle, apparently lawless conduct by the camp managers, as well as some humor from what was still wild Florida.

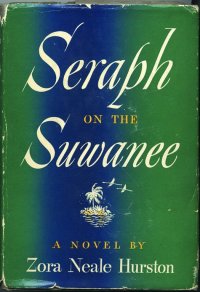

Seraph on the Suwanee

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1948

Hurston early on devised the strategy of blending folklore with her creative writing and continued it throughout her career. Seraph on the Suwanee, the story of Aury and Jim Meserve, upwardly mobile Crackers, was Hurston's final published book. The novel is located in a north Florida town, similar to Cross City, and in Polk County, and the shrimping community of New Smyrna, and draws heavily upon her knowledge of these locales from her folklore research. Jim Meserve, the main male character, is a turpentine woodsrider. Hurston had also worked in a Polk County phosphate mining camp in 1928 and written an unpublished, unperformed drama called "Polk County." Hurston early on devised the strategy of blending folklore with her creative writing and continued it throughout her career. Seraph on the Suwanee, the story of Aury and Jim Meserve, upwardly mobile Crackers, was Hurston's final published book. The novel is located in a north Florida town, similar to Cross City, and in Polk County, and the shrimping community of New Smyrna, and draws heavily upon her knowledge of these locales from her folklore research. Jim Meserve, the main male character, is a turpentine woodsrider. Hurston had also worked in a Polk County phosphate mining camp in 1928 and written an unpublished, unperformed drama called "Polk County."

In a daring and surprising move, Hurston made all the principal characters of Seraph on the Suwanee white. One criticism of the novel has been that the white characters speak a black idiom. In this note to friend, novelist Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, Hurston defends against this criticism by explaining her hypothesis, based on her experiences in Dixie County, location of Cross City, that the language of African Americans and poor whites is the same.

Lincoln Center Theater Presents

MULE BONE

by Langston Hughes & Zora Neale Hurston

Poster Artist: James McMullan

1991

Hurston and her close friend Langston Hughes collaborated on this Florida based folk drama of a quarrel between two friends. Based upon an Eatonville story, “The Bone of Contention,” by Hurston, the situation became just that when the authors quarreled over authorship and ownership of the rights to the play. The argument prevented production of the drama and ended, or at least serious ruptured the authors' friendship. Like much of Hurston's work, Mule Bone was never produced or published until many years after her death.

Hand Designed Christmas Card with note to Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings and Norton Baskin, December 1948, from the Rawlings Papers, University of Florida |